National Image of Ceramic Product Design in China, 1949-1966

Abstract

Background The early years of the People's Republic of China, 1949-1966, was a crucial period during the establishment of the socialist regime and image. Ceramic products, as a part of daily material culture, were deeply influenced by the national discourse. This article examines the significance of national images with regard to ceramic designs. The study examines Chinese ceramic products as a case study to show how ceramic design affected, constructed, and reproduced the national image in the early years of the PRC.

Methods From the perspective of material culture studies, initially, the specific background of Chinese society and Chinese identity through the national image at the time are reconstructed, based on a literature review of sociological and historical files, as well as magazine articles and news reports. Second, using products from the ceramic industry as specific case studies, the reproduction-construction relationship between ceramic products and the national image is analyzed.

Results Closeness to the daily and realistic life of the masses, providing service to the people, an emphasis on the new look of the socialist state, and an economic and practical style are the core elements of building China's national image during this period.

Conclusions An emphasis on the proletarian socialist state as a nascent regime is the label of the national image in China in 1949-1966. This represent the first element to influences the design of ceramic products. Expressions of decorative designs and subjects of ceramic products were closer to real-life scenes and tended to be simpler and more practical in terms of style, thus fitting the image positioning of New China at the time.

Keywords:

Ceramic Design, Socialism, National Image, Material Culture1. Introduction

In the narrative of design history as classified by country, the construction and identification of a national image through design and material culture frequently appear. An example is the Pevsnerian historiographic tradition, in which certain countries such as Britain, Italy, Germany, and the United States appeared to guide the developments of design history. However, a nation’s distinctive identity can never be known directly, but only approached through its forms of expression (Gimeno-Martínez, 2016). Design represents the opportunity to build a bridge between the national image and national expression considering this idea. The emphasis on national image is not only a cultural act, but also a political one. Any attempt to forge a national image is also a political action with political consequences (Smith, 1991). Political discourse, which is grounded in the national context, set in the metaphorical eye of the nation, and employed in the practice of representation, will typically flag nationhood (Billig, 1995).

The period of 1949-1966 is the special seventeen years in the history of the People's Republic of China, with a unique social background and political environment. This particular seventeen years period is now described with the term "the Seventeen Years." There are studies and discussions of this period in various fields, such as literature, film, aesthetics, and art, focusing on its relevance to politics. Cai (2016) explores the relationship between socialist literature and revolutionary narratives in 1949-1966. Ma (2016) within the sociopolitical context of the Seventeen Years explores the Chinese film industry, film professionals, and audiences negotiated with the authority of the party-state, and a centralized cultural system. Xue (2016) observes how Chinese art participated in the construction of national and state images and examines the stylistic evolution of artworks during the period. Therefore, given that ceramic as an object can reflect the main forces of cultural changes that affect a society (Arnold, 1997), the design expressions of ceramic products in this particular period are also worth studying.

The purpose of this study is to illustrate how national images and a country’s national identity are constructed and expressed in the designs of its ceramic products from the perspective of material culture studies, focusing on ceramics daily-use products in Jingdezhen city, China, from the period of 1949-1966 as the research object. Based on a literature review, first it is necessary to reproduce the situation of Chinese society and the identity of the national image through sociological, historical, and political research. Secondly, ceramic products are examined in case studies to show the relevance between the national image and expressions of designs of ceramic products at the time. By summarizing the design characteristics of ceramic products during the period, how the national image was constructed and recreated in ceramic products can be determined.

2. Background

2. 1. The Historical Division of Modern China

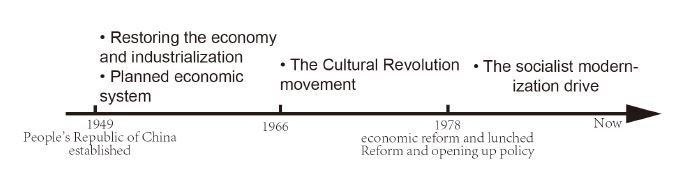

Looking at the history of the People's Republic of China (PRC), it can be largely divided into three different stages, with several key historical events as dividing points. The corresponding dates are 1949-1966, 1967-1977, and 1978 to the present, which correspond to the overall transformation of the country from political, economic to social.

Although the new regime was established by the Communist Party of China, the PRC was founded in 1949, and the new state still faced enormous challenges with regard to its internal and external environments due to a century of war and turmoil, depressed livelihoods, as well as the complex international situation. Influenced by traditional socialist economic theory and the Soviet experience, China established and operated a planned economic system in the early years of the country in order to restore the national economy and stabilize the regime quickly, as well as to meet the requirements of industrialization (Chen, 2001). The planned economy is an economic system which operates on the premise of socialized mass production, based on public ownership of the means of production, with the country's economy managed and regulated by the socialist state through directives and guiding plans according to the requirements of objective economic laws (Wu, 2003). However, owing to the nascent regime's inexperience and miscalculations, the government and the leadership changed their focus from economic to political fighting and launched the Cultural Revolution movement (1966-1976), resulting in a decade-long class struggle in Chinese society. Social and economic development as well as people’s lives nearly stagnated, and the whole country was plunged into chaos. The turning point in December of 1978 came when Deng Xiaoping, a second-generation leader of the PRC, introduced the economic reform program known as reform and opening up, which led to a return to economic development, after which Chinese society entered a period of modernization.

2. 2. National Image and New China National Image Reconstruction

A national image can be defined as a cognitive type of representation held by people of a given country, as what a person believes to be true about their nation and its people (Kunczik, 2016. p. 46). Just as nations are formed as imagined communities (Anderson, 2006), similarly, the image of the nation is constructed. The construction of a national image includes various factors, including those that are political, economic, military, cultural, geographical, historical, traditional and those related to its inhabitants (Zhao, 2006). During the aforementioned the Seventeen Years, however, the power of politics and government were decisive in the construction of the country's image and imagination. The interpretation of the national image consists of two perspectives: the self and the other. The former is the perception and impression of the domestic, while the latter is the image of China externally (international). Based on different positions, even the same image can be interpreted quite differently. It is important to note that the national image remains stable for a while but is not constant (Zhang, 2008). It changes with the context of society and with political and cultural development.

As the country that was the first to invent ceramics in history, with even the English name of the country – CHINA – referring to the country though the lower-case ‘china’ is synonymous with ceramics. Hence, ceramics seems to have a particular connection with the national image of China. For the PRC, founded in the mid-20th century, with a newborn regime and the Communist Party of China representing the worker-peasant proletariat as its leader, this unprecedented change made the need to build a new and different national image and identity of the people extremely important.

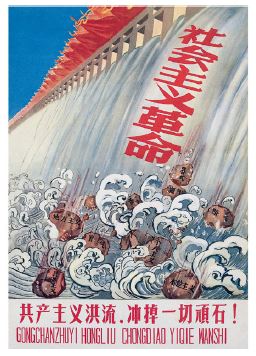

Due to the pursuit of the ideal of new socialism, ancient China underwent a comprehensive and profound social transition from 1949 until the mid-1960s, resulting in sweeping changes throughout the country. Shown in Figure 2 is a propaganda poster in 1958 with the title The Torrent of Communism Crashes All the Hard Stone. Hard stone here means the traditional negative values of society in the past, such as individualism, bureaucracy, and luxury. The most important feature that distinguishes China from the past during this period is that it is a socialist state led by the Communist Party of China, which represents the masses of the workers and peasants, unlike any other regime in China's thousands of years of history. The people-centered, national-interest-based collectivist values permeated the trends in the literary and art fields too. Then-leader Mao Zedong (1991: p846) proposed “Talks at the Yan'an Conference on Literature and Art” as early as May of 1942, emphasizing the priority of politics in literary and artistic creations: “ Proletarian literature and art is to serve the people and is part of the cause of proletarian liberation... Only by contacting and expressing the masses can work be meaningful…”. The talk was published on behalf of the Communist Party before the establishment of the new state, delivering the keynote of literary and artistic creation guidelines in the new China. Anderson (2006) introduces the term ‘official nationalism’, which is described as “something emanating from the state, and serving the interests of the state first and foremost.” In line with the interests of China as a socialist country and serving the people as the primary purpose, this cultural guideline has taken its own separate identity and has become a characteristic of socialist China.

Poster “The Torrent of Communism Crashes All the Hard Stone”* Images from Cushing, L., & Tompkins, A. (2007): p.28, p.41

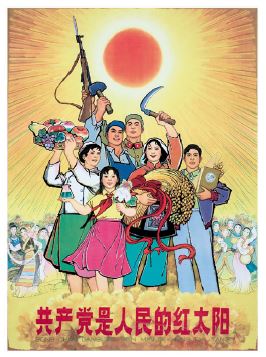

At the same time, the Chinese Communist Party’s philosophy and method of governing the country are closely connected with its background. As a new revolutionary tradition, the “class origin theory” has been inherited and developed (Gao, 2004). The first echelon of China's political class is the working class, followed by the peasants. The People's Liberation Army (PLA), also known as “Worker-peasant-soldiers”, was the pillar of the new regime (Gao, 2004). As shown in Figure 3, a poster made in 1964, which is a group portrait of people who represent and advocate the Communist Party and the Communists, links several representative class icons, with peasants, workers, and soldiers in the center of the picture. Hence, the reconstruction of the image and identity in the new China is inseparable from the concept of the proletarian masses.

Akin to the interests of the workers and peasants represented by the proletarian regime, artisans, who were at the bottom of the social stratum in the past, leaped to become the core of social change and the leading force in terms of their political treatment. During this period, the government bestowed the title of "Ceramic Artist" or "Ceramic Designer" onto artisans with outstanding skills, and the number of people awarded twice reached 296 (Jingdezhen, 2020). Using the cultural acquisition of collectivism, artisans reconstructed workers’ identities and established a set of new behavior habits, mental attitudes, and value beliefs in line with the identity. As a group of “new workers” with new minds, they relied on the process of creating and producing porcelain products, without exception, with the "socialist new ideas" stamp.

Therefore, the essential beliefs and values of socialism, specifically close to the daily lives of the masses, serving the people, stressing the new look of the socialist country, reflecting the real-life and economic and practical style, becoming the new image and identity representing the new regime of the mass proletariat, are the core elements in the building of the national image of the PRC.

3. National Image, Government Policies and Ceramic products

3. 1. The Reform in Ceramic Industry

During the period 1949-1966, under planned economy system, the Chinese government continued its socialist transformation of the ownership of the means of production in various industries. Under the proletarian regime, public ownership of the means of production became the primary task of establishing the people's democratic socialist society. Therefore, the socialist public transformation in Jingdezhen's ceramics industry, under the guidance of the central government and local governments, gradually implemented the transformation steps of the means of production, as follows. From 1951 to 1954, the Jingdezhen porcelain industry adopted the business model of private-private partnerships and cooperatives. From 1955 to 1956, the Jingdezhen porcelain industry entered into public-private partnerships. In 1958, public-private joint ventures and cooperatives in the porcelain industry began to shift to a state-owned business model. It was after January of 1959 that the Jingdezhen Porcelain Industry entered the national ownership system, and the establishment of the Jingdezhen Top Ten Porcelain Factories were announced (Jingdezhen, 2020). At this time, the proportion of the private economy in the porcelain business of Jingdezhen disappeared, and it entered the period of state planning and management. In the context of the socialist transformation process, national power has gradually penetrated the ceramics industry in Jingdezhen, while the country’s needs and tasks are closely linked with the development of the ceramics industry. With the shift from small, numerous, and scattered private to large state-owned ceramics factories under the guidance, assistance and planning of the government, the ceramics industry was rapidly upgraded to mechanized, modern industrial production.

Compared to porcelain crafts during the traditional Chinese dynasties, especially the Ming and Qing, Jingdezhen, as the most important porcelain center in China and the world, had the characteristics of a premodern society industry with large-scale production and the division of labor (Ledderose, 2001). However, this was in contrast to the state-owned porcelain factories in the new China. First, in terms of production owners, the porcelain-making industry of the past was a system in which the official kilns were owned by feudal dynasties, and the purpose of production was to serve the aristocracy and bureaucracy in the upper class, whereas the state-run porcelain factories in new China, owned by the government under the leadership of the Communist Party of China, represented the masses and aimed to serve the people. Secondly, the traditional porcelain-making process in Jingdezhen involved “72 processes;” i.e., a ceramic product needed to go through 72 different steps to be completed. Such a complex procedure incurs extremely high production costs and requires time, but the goal of the state-owned porcelain factories is to reduce production costs and produce products of high quality at a low price. Third, in line with the pace of industrialization, the development of the porcelain industry was from manual, to semi-manual, and then to mechanized. After the completion of the state-owned porcelain factory on August 1, 1954, the establishment of the Jingdezhen Ceramic Research Institute, which is the first ceramic research institution in the history of Jingdezhen ceramics (Xu, 1993), aimed to combine ceramics industry materials and technology research. Therefore, the socialist reform of the ceramic industry opened up a new mode of ceramics production and had an impact on the design expressions of ceramics.

3. 2. Tradition, Modernization of New China and Translation

Unlike the dichotomy in the political sphere, for arts and crafts with a thousand years of history and tradition, despite the new ideas, concepts, and even world views in the minds of the revolutionaries, the Chinese continue to demonstrate an uncommon consciousness of continuity and history in their lives (Fairbank & MacFarquhar, 2008). The porcelain industry, as one of the crafts with deep traditional imprints, continues the influence of thousands of years of ceramics craftsmanship, modeling, and decoration. It is impossible to completely eliminate it immediately, and there is no need to do so. Regarding the exploration of the relationship between tradition and modernity in literature, arts and crafts, the official discourse and advocacy guidelines at that time focused on the idea in the sentence “Valuable things of the ancient times can be used to learn from today, and the good things of foreign countries can be used for us as well.” In “Hundred Flowers Movement,” referring to the basis of official recognition, to some extent in the fields of literary, art, and culture, the free development of different schools and styles is recognized. Those voices reveal that the official attitude towards the tradition at that time was not blindly to deny and reject everything but rather to keep a more open position and to encourage innovation by combining the new image of the state to integrate traditions. As is necessary for the inheritance of the traditional, according to Gimeno-Martínez (2016), national art can reconstruct national images on the basis of its qualities.

The official guidelines present the expectation of new designs and forms of expression of tradition, forming a connection between the traditions of the past and a future-oriented national identity. On the one hand, there is a connection to the typical Chinese traditional culture and forms of expressions in the past, specifically the concept of the 'invention of tradition' proposed by historians Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (1983), where novel situations that take the form of a reference to old situations attempt to establish continuity with a suitable historic past. On the other hand, 'future-oriented' is a new characteristic separate from the past (Gimeno-Martínez, 2016) joined with the expectations of a promising future, which here refers to the expectation of the new modern China for the future development and image of the country.

3. 3. Expressions of the National Image in Ceramic Products

In China during the planned economy era, the state government, as the only organizer and distributor of production, merged the interests of the state with the well-being of the proletarian masses, designing for the state and the government, that is, for the masses. The ideology and values of the entire country and society were relatively unified. The design elements of ceramic products are mainly expressed through the shape and decoration of the products. Daily-use ceramics under industrialization include products with use-value in everyday life, such as tableware, coffee sets, tea sets, and wine sets. Carrying the concept of designing for the new China and socialism, ceramic designs during the Seventeen Years, decorative subjects and image styles depict characteristics that are different from the traditions of the past. The decorative elements and image styles carried by ceramics object in line with socialist values and imagination evoke a mental effect or thought in the mind of the user, reinforcing the national image of new China and the new society in people's minds. In order to distinguish between aristocratic and bureaucratic tastes in ceramic decorations of the dynasties of the past, including the patterns of dragons, phoenixes or sacred beasts, ceramics designers of the new China held an image reform movement to highlight the spirit of the new era. Jingdezhen ceramic products design formed a combined socialism and realism decorative style, and the design expressions showed new features.

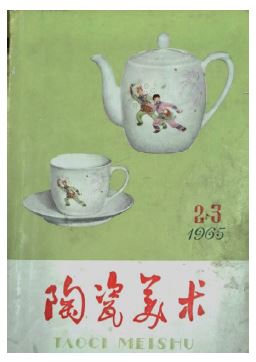

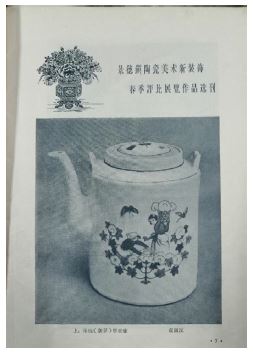

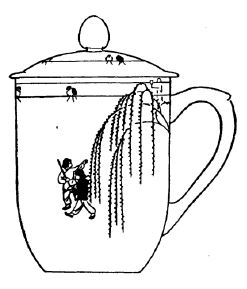

In the design of ceramics products, many creations were directly realistic or imitated the life and labor scenes of the peasants and workers of that time, as well as reflecting the real-life images of the masses in the new society. The decoration of figure subjects became extremely popular. Unlike traditional ceramics decorations that showed static and aesthetic figures of the time, the figures drawn on porcelain were full of movement and vitality, and there were a large number of decorative paradigms depicting scenes of people at work. This style was frequently published and appeared in ceramics-related magazines at that time. As shown in Figure 4, the cover of the second issue of Ceramic Art Magazine in 1965 featured a daily-use porcelain tea set design called the "Celebration Yaogu" (Waist Drum). The chosen decorative subject is a man and a woman, two farmers, beating a drum (a traditional instrument in northern Shanxi) to celebrate the harvest. The moment involved in the beating of the drum is chosen as a freeze-frame image, the picture overall is energetic and vibrant. In the 1965 "Jingdezhen Ceramic Art New Decoration Spring Competition Exhibition" series of works, a large number of works depicting labor scenes were selected and published in the magazine. An example is the teapot "cotton picking" (Figure 5), where a labor scene of farmers picking cotton is re-created as a picture to decorate a daily tea set. The editor of Ceramic Art Magazine noted in the final editorial (1965): "The exhibits are designed with attention to suit the use and appreciation requirements of the masses of workers, peasants and soldiers, and are a good start in the revolutionization of ceramic art and design."

Moreover, the designs of ceramic product decoration images, adding more real-life elements and themes, showed the new society and new view of life. In the February 1964 issue of The Porcelain Journal, the manuscript and description of "Spring Morning" was published, a teacup design by the ceramic product designer Yuan Dizhong, visually reflecting the designer's efforts and attempts consciously to select realistic subjects for daily porcelain decorative designs at the time. As shown in Figure 6, the decorative design of the cup includes electric wires and poles (upper right corner of the cup). It is intended that the electric wires and poles depict and convey life in the rural areas of Chinese society, where electrical devices were available. The use of electricity, at least at that time, signified the fact that living conditions were improving. As the designer Yuan (1964) explains in his composition, “The theme is to depict a pair of rural women going to work on a spring morning with the sunrise, and at the same time to show the new face of rural life.” In addition, the methods of taking the design elements of ceramic products from real life and subjects is not simply a reproduction of reality. More importantly, it contains the sentiment of praise and confidence representing the life of new China, conveying a positive value orientation and judgment. As Figure 7 shows, the ceramic plate is decorated with a picture depicting a bumper crop, while the two children on the left are counting the amount of grain. This slightly exaggerated decorative image of grain piled up in the "C" shaped composition and extending into the distance is called "countless", and is full of admiration for the bumper harvest under the new life.

This conscious design based on real-life, such as the celebrating peasants, the labor scenes, the electric wires, and poles, all carry a distinct meaning. The reproduction and dissemination of these distinctive realistic subjects through ceramic products represented the conscious reinforcement and propagation of the image of the new socialist China.

Unlike traditional ceramic products with complex and exquisite patterns spread over surfaces of utensils, during that time, designs presented the use of traditional patterns as basic design elements, and through these patterns reconstructed the design to show a clear, simple and generous layout. That is, new forms were created within the traditional style. The reason for this change is more than the scientific and rational requirements of industrial mass production and the technical effects of decal making. More important are the simple, practical, and plain product features that match the aesthetic values of the new China and at the same time can be used by a wider range of people.

The styles of expression forms and the decorative designs in the field of arts and crafts creation at the time were critiqued in an article entitled "The Problem of the Direction of Arts and Crafts" published in the People's Daily on July 29, 1957. "Arts and crafts are a valuable national heritage… They are endowed with 'socialist content, national form' to create a new art style rich in national characteristics… some crafts in the design of the pursuit are exquisite but overly processed, with high production costs, and are less practical such that the masses can enjoy them but they are beyond use." The highly complex style of decoration was particularly prevalent in the Qing Dynasty. For decorative motifs, owing to the long history of ceramics, popular motifs and patterns tend to be repeated in different dynasties and periods. Depending on the aesthetic taste of the era, even the same subject motifs can be presented with different decorative styles. Taking the most popular traditional Chinese interlocking branch lotus as an example, decorative designs of ceramic products with the lotus pattern in new China during the Seventeen Years changed significantly compared to the previous forms.

The Interlocking lotus pattern is based on the lotus flower, surrounded by vines and scroll grass to form the pattern. It emerged in the Song Dynasty and was popular in the Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties. The pattern is used widely on surface decorations of ceramic objects such as plates, bowls, bottles, pots, cups, and incense burners. As shown in Table 1, the previous design of the lotus pattern is dominated by a complex form of decoration covering the surface of the vessel, which is extremely delicate and dazzling to the eyes. As the article criticizing arts and crafts points out, crafts that are so gorgeous only can be enjoyed but cannot be touched. In contrast, the decorations of the lotus pattern tableware produced in 1960 were markedly simplified in terms of tableware design were under industrial production. The "S"-shaped main branch line ingeniously unites the lotus, branches, and leaves, and the primary and secondary patterns are distinct. The decoration of the tableware is only shown in the mouth area of the utensil, leaving the center part, which holds the food, white so as to ensure both its practically (decoration not necessary for the used part) and its attractiveness (ornamental pattern for the non-use part).

In addition to learning from traditional designs, the form of the expression of the motifs had also been innovated. Unlike changing the composition and decorative layout, the expression of the image on the surface of the utensils was also preferred to be realistic and vivid, re-inscribing the decorative back to life with authenticity, rather than two-dimensional flat patterns. Taking the stylistic changes of the grape motif as an example, Figure 8 shows a blue-and-white grape plate designed by the Ceramic Institute in 1955, and Figure 9 shows a traditional blue and white grape dish from the Ming Dynasty. Although the same decorative grape is chosen, there are obvious differences in the presentation of the subject. The picture design of the plate in the new period removes the cumbersome and irrelevant ornamentation of the subject. The grapes, vines, and leaves are interlaced to reproduce the original growing situation of grapes vividly. Compared with beauty, or simple decoration, what is more important is the realist aesthetic of depicting and displaying the real world.

Grape pattern plate in new China* Images from Jingdezhen Ceramics, 2020 (01). p.36 and Sotheby's website.

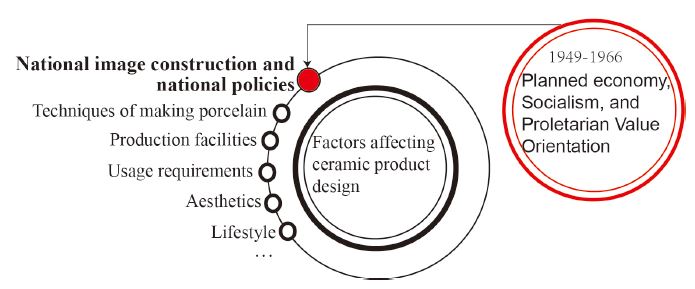

In summary, during one of the most authoritative and controlling periods for the Chinese government, ceramic tableware designs took on a form of expression that distinguished itself from both the traditional and contemporary. The product of the Seventeen Years, accompanied by the unique political, economic and social landscape of China at that time, creates a distinct landscape of the ceramics culture in the second half of the twentieth century. Although there are various factors affecting product designs, including improvements in manufacturing technologies, changes in lifestyles, and new consumer demands, among others, the images and discourse of the country at that time are the most important factors intervening in and influencing ceramic designs. The design concepts, expressions and aesthetic value orientations of ceramic products were all profoundly influenced.

In line with the slogans and advocacies such as "being close to the people," "creating for the people," and "the new look of socialism," which arose in official policies and propaganda constantly, ceramic products, as "banal objects" for everyday use, were a medium that appeared in daily life on a regular basis due to practical and functional necessities, and they could play a significant role in the expression of a new image under Chinese propaganda. Through the designs of the image expressions of ceramic products and the common cultural landscape when aligned with the unprecedented unified, single ideology and social atmosphere under the background of socialist construction, such designs can easily be interpreted in the minds of people (viewers and users) and evoke the imagination of new China.

4. Conclusion

Design, as a tool and means to convey the national image and national identity, is reflected in the formal expressions of various materials and cultural products to convey and strengthen the performance of the national image. One of the issues that deserves scrutiny is the difference between how the nation has been conceptualized and how it has been reproduced, performed, and experienced (Gimeno-Martínez, 2016). During the period of 1949-1966 in China, national image construction and propaganda intervened and influenced ceramic product design as the most important factors. The construction of the nation’s conceptualization cannot be divorced from the government's top-down policy, propaganda, and position of power among the people. As a result, ceramic product designs were prompted to have a clear value, aesthetic orientation and to consider the position of the user. Ceramic culture occupies a unique position in Chinese culture, as it is both deeply rooted in history and rich in national symbols. The observation of ceramic products changes under the new Chinese regime and reveals how the Chinese government and state forces were infiltrating and influencing designs at the time, while also seeking a balance between tradition and modernity.

Ended feudal autocracies that lasted for more than 2,000 years and ending hundreds of years of war, with the successful establishment of a unified proletarian state representing the masses of the people, the entire country and its people were filled with optimism and imagination for the charming future, and the desire to build a sense of belonging and identification with the state and nation was constantly strengthened. During 1949-1966, as a nascent regime and proletarian socialist state, the unique label permeated the ideology and values of the entire period. Ceramic product design trends followed the direction of official policies and guidances and spoke of the image of China as a modern socialist state. Ceramic designs were inspired more by the daily production and life of the masses, shifting the patterns of ceramic product expressions from decorative to realistic while also abandoning cumbersome and complex patterns to make the products simpler and more practical. All of these reforms were intended to forge a better alignment with the values espoused and promoted by the new regime. Therefore, even if ceramic products are used as everyday objects, the designs and decorative forms of ceramic products could change to offer a different national image and identity to represent the new China.

Notes

Copyright : This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), which permits unrestricted educational and non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso books.

- Arnold, D. (1997). Ceramic theory and cultural process. Cambridge (GB): New York; Melbourne: Cambridge university press.

- Billig, M. (1995). Banal nationalism. London: The Cromwell Press Ltd.

- Beijing Art Museum (eds)(2013). 薪火相传:景德镇1949~1980年瓷器艺术 [The Ceramic Art of Jingdezhen 1949-1980]. 北京: 北京美术摄影出版社.

-

Cai, X. (2016). Revolution and its narratives. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822374619]

- Ceramic Art Magazine. (1965). No2-3. Jingdezhen: Jingdezhen Ceramic Art Workers Association.

- Cushing, L., & Tompkins, A. (2007). Chinese posters. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

- Chen, Y. J. (2001). 中国为什么在 50 年代选择了计划经济体制 [Why Did China Choose the System of Planned Economy in the 1950s]. JOURNAL OF XIAMEN UNIVERSITY (Arts &Social Sciences), 146(2), 56-64.

- Fairbank, J., & MacFarquhar, R. (2008). The People's Republic ; Part 1. The emergence of revolutionary China 1949-1965. Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Gao. H. (2004). 身份和差異:1949-1965年中國社會的政治分層 [Status and Difference: Political Stratification in China, 1949-1965]. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Institute of Asia-pacific Studies.

-

Gimeno-Martínez, J. (2016). Design and national identity. Bloomsbury Publishing.

[https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474287302]

- Hobsbawm. E, & Ranger. T. (eds) (1983) The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

- Jingdezhen Porcelain Factory Museum. (eds)(2020). 国窑·景德镇十大瓷厂风华录[GUOYAO: Jingdezhen top ten porcelain factory records]. 北京:中国文史出版社.

- Jingdezhen Porcelain History committee (eds)(2019). 景德镇陶瓷史料(上册) [Historical records of Jingdezhen Ceramics (Volume Ⅰ:1949-1978)]. 南昌:江西人民出版社.

- Kunczik, M. (2016). Images of Nations and International Public Relations. Routledge.

- Ledderose, L. (2001). Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art. Princeton University Press.

- Mao. Z. D. (1991). 毛泽东选集(第三卷) [Selected works of Mao Tse-tung Ⅲ]. 北京: 人民出版社.

-

Ma, R. (2016). A genealogy of film festivals in the People's Republic of China: 'film weeks' during the 'Seventeen Years' (1949-1966). New Review Of Film And Television Studies, 14(1), 40-58.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/17400309.2015.1107266]

- Smith, A. D. (1991). National identity. London: Penguin.

- The Problem of the Direction of Arts and Crafts. (1957, July). The People's Daily, Retrieved from https://cn.govopendata.com/renminribao/1957/7/29/1/.

-

Worden, S. (2009). Aluminium and Contemporary Australian Design: Materials History, Cultural and National Identity. Journal of Design History, 22(2), 151-171.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/epn039]

- Wu, L. (2003). 中国计划经济的重新审视与评价 [China's Planned Economy Reconsidered and Reassessed]. Contemporary China History Studies, 10(4),37-46.

- Xue, Y. J. (2016). 国民与国家形象塑造: 十七年(1949-1966)美术研究 [Nationals and the National Image Shaping: Fine Arts in the Seventeen Year(1949-1966)] (Doctoral dissertation). Available from CNKI database.

- Xu, X. Z. (eds) (1993). 景镇陶瓷科技大事记(ニ) [Jingdezhen ceramic technology events]. Jingdezhen Ceramics, 1993(04), 57-61.

- Yang, Y. F. (1991). 景德镇陶瓷古今谈 [the Talk on Jingdezhen Ceramics from Ancient to Modern]. 北京:中国文史出版社.

- Yuan. D. Z. (1964). 談"春晨"画面的創作和休会 [Talking about the creation and experience of the "Spring Morning"]. The Porcelain Journal, 1964(02), 44-45.

- Zhao, X. B. (2006). 关于国家形象等概念的理解 [Understanding of the concept of national image]. Modern Communication(Journal of Communication University of China), 2006, (05), 63-65.

- Zhang, F. (2008). 国家形象概论 [Introduction to national image]. Literary and Artistic Contention, 2008, (07), 23-29.